|

|

|

|

|

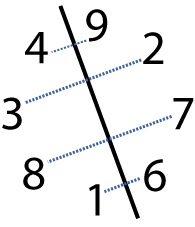

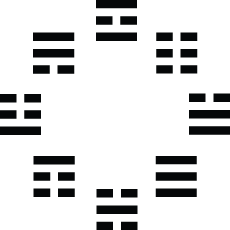

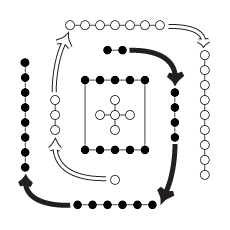

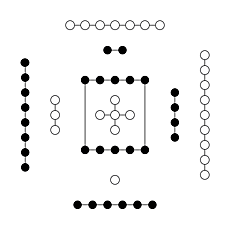

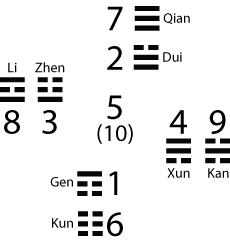

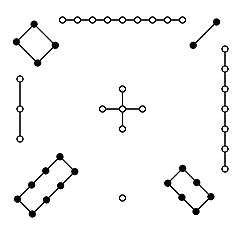

Hetu |

Luoshu |

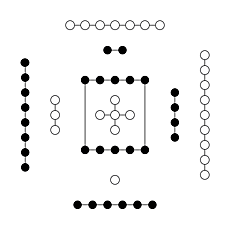

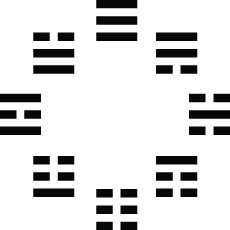

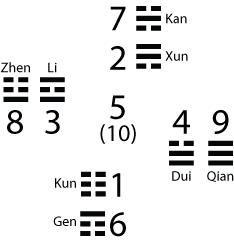

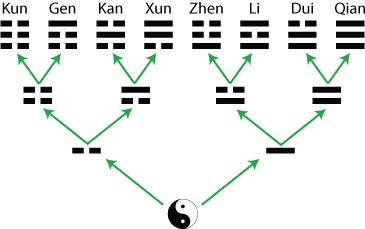

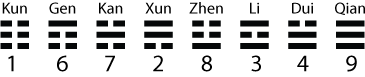

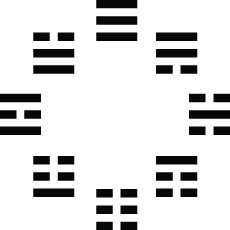

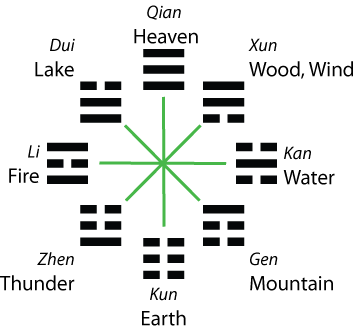

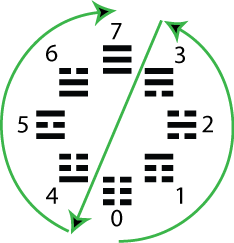

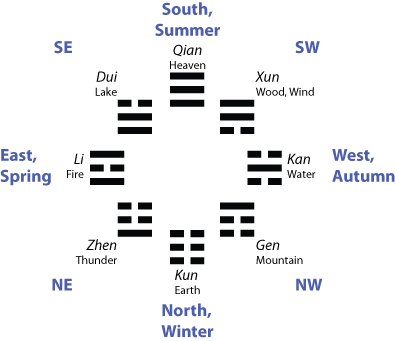

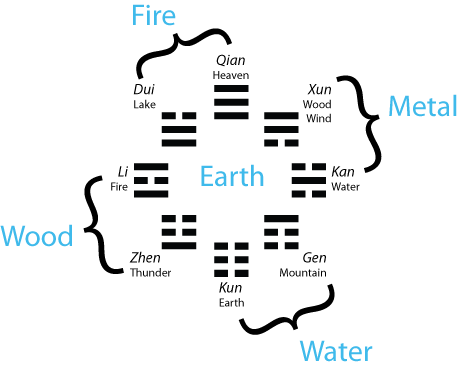

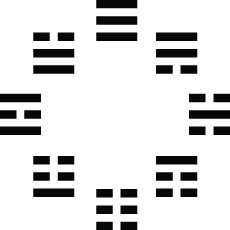

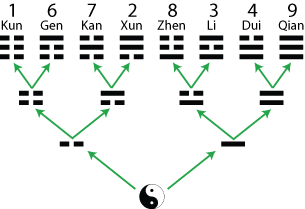

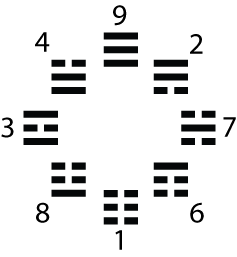

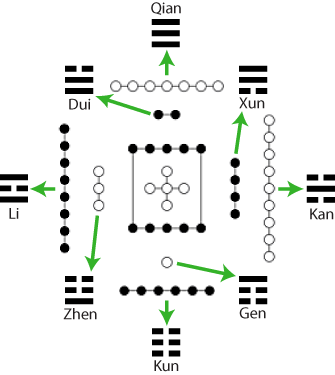

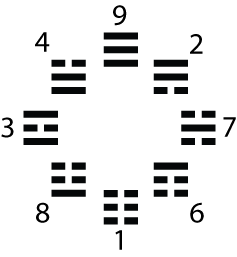

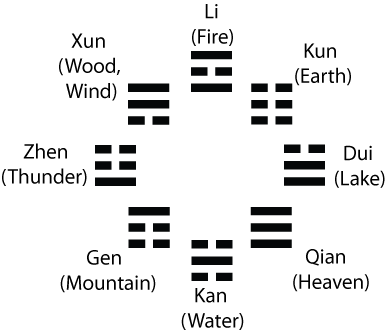

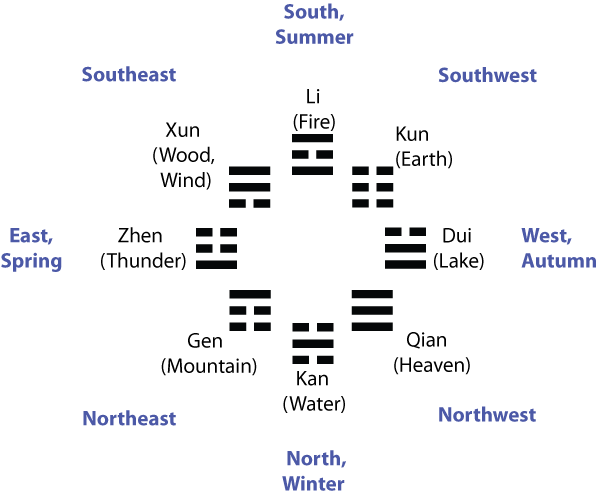

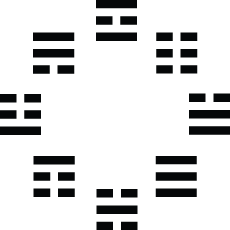

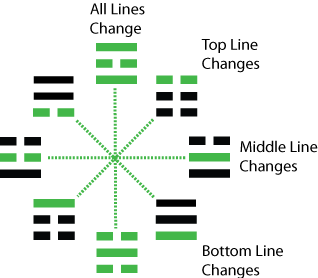

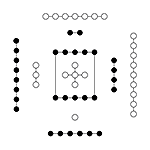

The others are cyclic arrangements of the eight trigrams, called the Before Heaven (Xiantiantu) and the After Heaven (Houtiantu) arrangements:

|

|

|

Before Heaven |

After Heaven |

These diagrams are traditionally thought to illustrate ideas about the trigrams, their meanings, their cyclic appearance in worldly phenomena, and their use in interpreting the I Ching hexagrams, which are composed of two trigrams apiece.

There is considerable doubt about the origins and actual ages of these diagrams. Tradition ascribes their discovery to ancient sage kings such as Fuxi and King Wen, who made use of them in creating the oldest layer of I Ching (the hexagram and line statements, known as the Zhouyi). However, modern scholars tend to believe these diagrams are later inventions that were created to help interpret the Zhouyi. It is even uncertain whether the Zhouyi authors had much awareness of trigrams or used them in determining the meanings of the hexagrams.[fn01] If trigrams are a later invention, then the river diagrams and trigram cycles are presumably later still.

I will cite the conclusions of modern scholarship about the probable dates of these diagrams. If you prefer to believe the older dates ascribed traditionally, I hope you will forgive me and that you will still find some information of interest in this article.

Regardless of their age or origins, these diagrams are a rich source of interpretive ideas about the I Ching. While we do not know the thought processes that of their creators, the structure of the diagrams themselves raises certain possibilities. Some of these issues have been discussed by traditional commentators, as well as modern authors such as Alfred Huang.[fn02] The purpose of this article is partly to highlight some of the traditional ideas about the structure of these diagrams. More importantly, I will point out some correspondences and symmetries that are rarely mentioned, or that have never been mentioned before, to the best of my knowledge.

The Hetu (Yellow River Map)

The Hetu is supposed to have first appeared as a pattern on the back of a dragon-horse that emerged from the Yellow River and appeared to the ancient sage-king Fuxi. According to legend, Fuxi was the first king of China and lived ca. 2000 BC.[fn03] However, Bent Nielsen suggests that it may have been Chen Tuan (d. 989 AD) or Shao Yong (1011–1077 AD) who first attributed the Hetu to Fuxi.[fn04]

We do not know when the Hetu was invented, but Richard J. Smith tells us that it was referred to by documents in the late Zhou (777 BC - 221 BC) period. There is also a reference in the Dazhuan or Great Commentary of the I Ching (finalized by 168 BC), I.11.8: "The Ho gave forth the map . . ." There is evidence that the Hetu was already being compared with the trigrams in Han dynasty times (206 BC–220 AD). However, the earliest surviving illustrations are from the 10th century AD.[fn05]

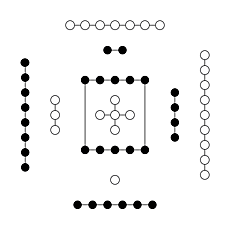

The map is drawn as clusters of white and black dots that represent numbers. Below is the map itself and a list of the numbers that correspond to each set of dots.

|

|

|

Hetu Map |

Hetu Numbers |

The map includes the numbers from 1 through 10. White dots represent the odd numbers, and black dots represent the even numbers. The number 10 is represented by the square near the center that has two sets of five black dots each. The white and black coloring corresponds with the Great Commentary, which states that odd numbers belong to heaven, and even numbers to earth:

Heaven has 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9.

Earth has 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10.

—Great Commentary I:9:1 [fn06]

The following passage is often taken to be a reference to the Hetu, although it may simply be about the numbers 1 through 10, rather than about the Hetu arrangement of those numbers:

Thus heaven has five numbers

and earth has five numbers.

The two series are interlocked in order;

each number in one series has its partner in the other.

The sum of heaven's numbers is 25;

the sum of earth's numbers is 30;

the sum of the numbers of heaven and earth is 55.

This is what stimulates alternation and transformation

and animates spirits.

—Great Commentary I:9:2 [fn07]

If you look the groups of white dots numbered 1, 3, 7, and 9, they form a clockwise spiral. Similarly, the black dots numbered 2, 4, 6, and 8, form a clockwise spiral. These two spirals together bear some resemblance to the Taijitu, or Yin Yang symbol, though the Taijitu was not invented until Song Dynasty times, by philosopher Zhou Dunyi (1017–1073 AD).[fn08]

|

|

|

Hetu Spirals |

Taijitu |

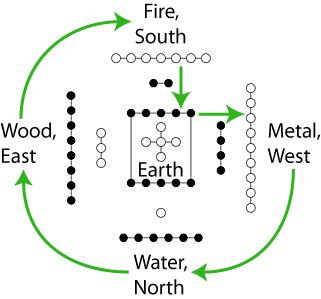

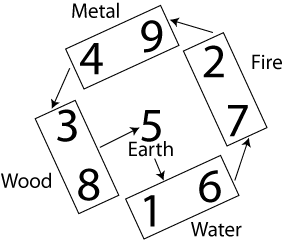

The Hetu and Five Phase Theory

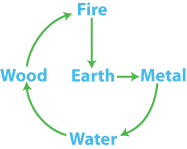

Each pair of adjacent numbers differs by 5: that is, 1 and 6, 3 and 8, 2 and 7, 4 and 9. These pairings relate the Hetu to Five Phase (Wu Xing) theory. Dong Zhongshu, writing c. 135 BC, wrote of the Five Phases in terms of their positions in the Hetu:

Wood dwells on the left, Metal on the right, Fire in front and Water behind, with Earth in the middle.[fn09]

These positions arise from the numbers traditionally assigned to the Phases in Five Phase theory. The Five Phases were ordered in various ways in order to portray differing types of relationships. The numbering of the Phases is taken from what Joseph Needham calls the Cosmogonic Order, "the evolutionary order in which the elements were supposed to have come into being."[fn10] The order is Water, Fire, Wood, Metal, Earth; these are assigned to the numbers 1 through 5, and then over again to the numbers 6 through 10. The result, as listed by Ho Peng Yoke[fn11], is

| Water | 1 and 6 | North |

| Fire | 2 and 7 | South |

| Wood | 3 and 8 | East |

| Metal | 4 and 9 | West |

| Earth | 5 and 10 | Center |

Stuart Alve Olson refers to the first number in each pair as the Production number, and the second number as the Completion number. Thus, the Water element is produced by 1 and completed by 6, the Fire Element is produced by 2 and completed by 7, and so forth.[fn12]

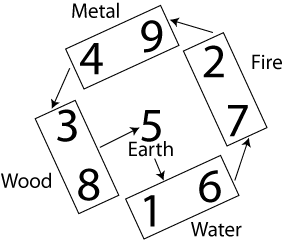

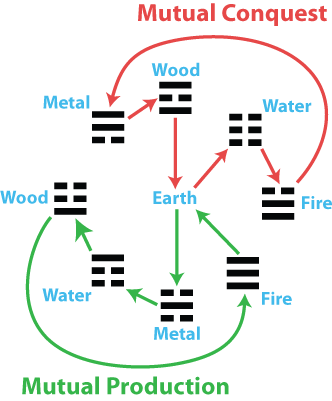

However, though the Five Phases are numbered in Cosmogonic order, they are arranged in the Hetu in a different order, which Needham calls the Mutual Production order. In this order, each Phase gives rise to the next one, and together they form a cycle of gradually increasing yang followed by gradually increasing yin. This cycle resembles the annual order of the seasons and the daily cycle of day and night. The order is Wood (3 and 8), Fire (2 and 7), Earth (5 and 10), Metal (4 and 9), and Water (1 and 6).[fn13] Earth is considered to be the balanced state, so it is placed in the center of the diagram.

Hetu and Trigram Assignments

The writers Alfred Huang and Stuart Alve Olson [fn14] both associate trigrams with the Hetu diagram in the following positions:

|

|

|

Hetu Map |

Trigram Assignments |

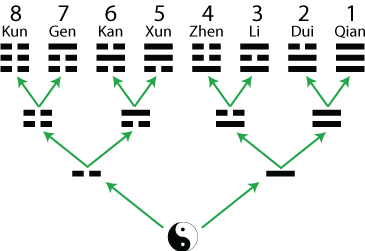

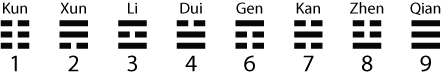

Huang states that it was Shao Yong who figured out how the Hetu Map corresponds to the trigrams. The first step is to order the trigrams as they appear when generated systematically from the bottom line up. Each time you add another line, you put the yin line on the left and the yang line on the right. In the resulting sequence, the trigrams progress from the most yin ![]() Kun)

Kun)![]() Qian) as you move from left to right.

Qian) as you move from left to right.

This method of generating the trigrams is probably inspired by the following passage in the Great Commentary:

Thus:

Yi holds the Ultimate Limit,

whence spring the Two Primal Forces, yang and yin,

The Two Forces generate four diagrams,

and the four diagrams generate eight trigrams.

—Great Commentary I:11:5 [fn15]

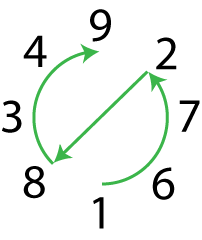

Then Shao Yong apparently overlaid the following numbers onto this trigram sequence: 1, 6, 7, 2, 8, 3, 4, 9. Huang calls these "symbolic numbers," but doesn't explain where the number sequence came from. However, I believe they must have come from the Luoshu. We'll be looking at the Luoshu in more detail later. For now, simply note that the following path through the Luoshu numbers results in the sequence that Huang calls the "symbolic numbers." If you think of 9 as being in the most yang position in the sequence, and 1 as being in the most yin position, then this path seems to show a gradual progress from yin to yang.

When you overlay this number sequence on the trigram sequence shown previously, the result is the following pairings of numbers and trigrams:

Then, if you assign each trigram to its matching number in the Hetu diagram, you get the arrangement of trigrams shown at the start of this section.

For various reasons, I think that this method of assigning trigrams to the Hetu diagram is a poor one, even if it did originate with Shao Yong. We'll return to this topic after examining the Before Heaven trigram cycle. For now, just remember to view this set of trigram/Hetu assignments with a grain of salt.

The Before Heaven Trigram Cycle

Ritsema and Sabbadini summarize a common view when they state "the 8 trigrams can be arranged in a cyclical order in two main ways. The older one is called the Sequence of Earlier Heaven or the Primal Arrangement. It is traditionally attributed to Fu Xi and it reflects a cosmic order prior to the human world. In it the trigrams form simple pairs of opposites at the end of each diameter." [fn16]

Richard Wilhelm associates this arrangement with the following passage in the Shuogua (5th-3rd Centuries BC)[fn17] appendix of the I Ching:

Heaven and earth determine the direction. The forces of mountain and lake are united. Thunder and wind arouse each other. Water and fire do not combat each other. Thus are the eight trigrams intermingled.[fn18]

The resemblance of this passage to the Before Heaven sequence is clearer if we add the traditional nature image names to each trigram.

From this image, you can see that the members of each pair listed in the Shuogua (Heaven and Earth, Mountain and Lake, etc.) are diametrically opposite each other. Some of the associated nature images also seem like opposites, such as Heaven and Earth, or Fire and Water. Further, you can see that the trigrams in each pair are structural complements of each other. That is, you can derive the second trigram by reversing the polarity of each line in the first trigram, from yang to yin or from yin to yang. For example, in the pair ![]() Dui (Lake) and

Dui (Lake) and ![]() Gen (Mountain), the bottom line changes from yang to yin, the middle line also changes from yang to yin, and the top line changes from yin to yang.

Gen (Mountain), the bottom line changes from yang to yin, the middle line also changes from yang to yin, and the top line changes from yin to yang.

Nevertheless, it is not clear whether the authors of the Shuogua really had the Before Heaven sequence in mind when they wrote this passage. Bent Nielsen points out that "no commentators prior to the Song dynasty [1127–1279] interpreted this passage as a description of a trigram cycle."[fn19] Also, the Shuogua includes mentions of other sequences of opposed trigram pairs that never came to be interpreted as a cycle.

Richard Rutt states that, contrary to the legend that attributes the Before Heaven cycle to Fuxi, "This order is probably a creation of the Song period, and does not appear in the Shuogua."[fn20]

Nielsen further states:

The only characteristic feature of Zhu Xi’s Xiantiantu [Before Heaven] arrangement is that the trigrams are paired according to the pang tong 旁通, laterally linked, principle, which means the yang lines in the first trigram of a pair turns into a yin line in the second trigram and vice versa. The two trigrams are then placed opposite each other on the circle. There is therefore no compelling logic or other obvious reasons why one of the four series [of pairs of opposite trigrams] mentioned above should be preferred to the others.[fn21]

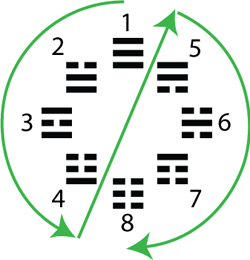

Here I think Nielsen is mistaken. There is a simple rationale for the order of the pairs in the Before Heaven sequence. It relates to the trigrams in the order that they are generated from one, to two, to three lines, as shown previously. Alfred Huang points out that if you number this sequence from 1 to 8, from Qian to Kun, then you get this pairing of trigrams and numbers: [fn22]

As Huang notes, when you apply these trigram numbers to the Before Heaven sequence, you get a pattern reminiscent of the Taijitu, or Yin Yang symbol:

|

|

The Taijitu "was first introduced by Song Dynasty philosopher Zhou Dunyi (周敦頤 1017–1073) in his Taijitu shuo 太極圖說."[fn23] If Rutt is correct, then Before Heaven is also a creation of the Song Dynasty, so perhaps the resemblance is not coincidental.

There are some other interesting properties in the Before Heaven cycle:

- The cardinal points (top and bottom, left and right) are occupied by the trigrams that are vertically symmetrical:

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  . You can flip any of these vertically and still have the same trigram.

. You can flip any of these vertically and still have the same trigram. - If you compare the upper left and lower left corners, both trigrams are composed of yin lines above yang lines. If you compare the upper right and lower right corners, both trigrams are composed of yang lines above yin lines.

- If you compare the upper left and upper right corners, the trigrams are the same except for being vertically flipped. If you compare the lower left and lower right corners, the trigrams are also the same except for being vertically flipped.

In general, Before Heaven is a highly balanced and symmetrical arrangement that shows a clear and gradual cycle from yin to yang and back to yin.

Before Heaven and Binary Numbers

It is now common to see the claim that the I Ching anticipates the binary notation invented by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, which in turn forms the number system underlying all modern computers.[fn24] People who think this way like to identify yin (broken) lines with the number 0, and yang (solid) lines with the number 1. If you accept this notion, then a trigram like ![]() Qian can be represented as 111,

Qian can be represented as 111, ![]() Dui as 110,

Dui as 110, ![]() Zhen as 100, and so forth. If you convert these binary numbers to their decimal equivalents, then the numbers for the Before Heaven sequence are as follows:[fn25]

Zhen as 100, and so forth. If you convert these binary numbers to their decimal equivalents, then the numbers for the Before Heaven sequence are as follows:[fn25]

This is almost the same numbering sequence that we discussed in the previous section, except that numbers go in the reverse direction, with the lowest number at ![]() Kun and the highest number at

Kun and the highest number at ![]() Qian. Also, the numbering sequence runs from 0 to 7 instead of from 1 to 8.

Qian. Also, the numbering sequence runs from 0 to 7 instead of from 1 to 8.

However, it is important to understand that the I Ching forms only a very imperfect analogy to binary numbering [fn26]:

- The ancient Chinese wrote their numbers in base 10.[fn27]

- They did not have a symbol for 0, but instead wrote their numbers in a grid and left a blank space to indicate that there was no value for a certain digit.[fn28]

- In earliest times, the Chinese seem to have associated a variety of different numbers with the two types of lines (yin or yang).[fn29]

- Later, they came to associate 6 with a changing yin line, 7 with a stable yang line, 8 with a stable yin line, and 9 with a changing yang line.[fn30]

- The accepted hexagram sequence does not place the hexagrams in order by their binary value. Nor does the other ancient hexagram sequence, the Mawangdui sequence.[fn31] The first person to order the hexagrams this way seems to have been Shao Yong, more than a thousand years after the I Ching was created.[fn32]

- Binary notation assigns different denominations to each digit, where from right to left, the denominations are 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, and so on. However, when you look at the hexagram meanings in the I Ching, there does not seem to be any sense that the bottom line is 32 times more important than the top line. For example, if you compare the meaning of

Displacing with

Displacing with  Heaven, where only the top line differs, the difference in meanings is dramatic even though, considered as binary numbers, their values are adjacent (62 and 63 in decimal equivalents).

Heaven, where only the top line differs, the difference in meanings is dramatic even though, considered as binary numbers, their values are adjacent (62 and 63 in decimal equivalents). - As Richard Rutt points out, "the Fuxi order as a binary series is no more than an automatic result of designing a complete series of hexagrams using only two elements. Any two symbols taken together will yield combinations and permutations that are capable of arrangement in binary counting order."[fn33]

- As Joseph Needham said, "The chief defect in the attribution of mathematical significance to the hexagrams is that nothing was further from the thought of ancient I Ching experts than any kind of quantitative calculation . . . One must surely ask of any invention, whether mathematical or mechanical, that it be made consciously and for use."[fn34]

To avoid misleading implications, I think it is better to not use 0 and 1 to represent yin and yang lines. If you want to use numbers to represent lines, it would make more sense to use 7 and 8, the numbers that eventually came to represent young yang and yin lines. (The numbers 6 and 9 would be less appropriate, since they really imply changing lines.) Another possibility would be to use the numbers 1 and 8; Fendos tells us that the yang (![]() ) and yin (

) and yin (![]() ) lines may have originally taken their form from the characters for 1 and 8.[fn35]

) lines may have originally taken their form from the characters for 1 and 8.[fn35]

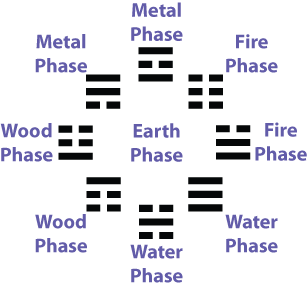

Before Heaven and the Five Phases

The Before Heaven sequence is commonly associated with the four directions and the seasons as follows:

This annual cycle corresponds well with the structural pattern of the trigrams, with the more yang trigrams allocated in the Spring and Summer, and the more yin trigrams allocated in the Autumn and Winter.

I haven't located any references that associate the Five Phases with the Before Heaven sequence, but it is common to associate the Five Phases with the seasons. Based on those seasonal assignments, the Five Phases would correlate with the Before Heaven sequence as follows:

You may notice some things about the trigram/five phase assignments that seem surprising. For example, what is the Fire trigram doing in the Wood phase, while the Lake trigram is in the Fire phase, the Water trigram is in the Metal phase, and the Earth trigram is in the Water phase? To reiterate, we combined the Five Phases with the Before Heaven cycle based on the associations that both systems have with the annual, seasonal cycle. Is it possible that the Five Phases and the I Ching trigrams are incompatible systems?

I think the systems are not actually incompatible. Both the Five Phases and the Eight Trigrams are expressions of various mixtures of Yin and Yang. However, the nature images referred to in each system should not be taken too literally. Instead, each nature image serves as a mnemonic for some aspect of the underlying meaning, and they signify different things in the two systems. For example, in the Five Phase system, Earth signifies an even balance of Yin and Yang energies, whereas in the Eight Trigrams, Earth signifies the extreme of Yin. Thus, to identify the Earth trigram with the Earth Phase would be a mistake.

It is important to remember that the nature images of the trigrams are not their actual names. Of the trigram names (Qian, Dui, Li, Zhen, Xun, Kan, Gen, Kun), Rutt tells us

No certain meanings can be given for the trigram names. The definitions given for them in character dictionaries are believed to be modern. They are most probably derived from the tags of the hexagrams that reduplicate each trigram . . . The hexagram tags themselves are exceedingly obscure.[fn36]

In the I Ching, the Shuogua appendix associates each trigram name with both a nature image and a xingqing or temperament. In Rutt's translation, these are as follows:[fn37]

| Name | Nature Image | Temperament |

| Qian | Heaven | Strong |

| Dui | Still water | Pleasing |

| Li | Fire | Connecting |

| Zhen | Thunder | Moving |

| Xun | Wind | Entering |

| Kan | Moving water | Sinking |

| Gen | Mountain | Stopping |

| Kun | Earth | Compliant |

The nature images could have been brought in to make the temperaments easier to visualize. For example, the image Thunder could have been chosen simply to remind you of the idea of sudden, intense movement. Similarly, Mountain could have been chosen as an example of something that is solidly planted and immoveable, thus suggesting the temperament of "Stopping."

A similar consideration applies to the names in the Five Phase system. Thus, Frank J. Swetz says:

The names of the phases are materials common and necessary in daily life: Water, Fire, Metal, Wood, and Earth. Each term does not designate the object itself but rather a type of transformation associated with the object. [fn38]

The following table gives Swetz's description of each of the Five Phases[fn39], along with Richard Rutt's translations for the names of the trigrams. If you compare the meanings rather than the nature images, the Five Phases in the Mutual Production order actually correspond well to the trigrams in Before Heaven order.

SEASONS |

Five Phases |

Eight Trigrams |

| Spring | Wood

|

Zhen |

Li Connecting Image: Fire |

||

| Summer | Fire "shoots energy upward, under its influence energy reaches a peak" |

Dui Pleasing Image: Lake |

Qian Strong Image: Heaven |

||

| Late Summer/Early Autumn, or else the transitions between each pair of seasons | Earth "moves cyclically and horizontally about an axis" |

None. The trigrams do not represent the Earth state. You can see this because the 5 or 10 in the center of the Hetu and Luoshu diagrams represents Earth, and does not get mapped to any trigrams. |

| Autumn | Metal "a dense, inward implosion of energy" |

Xun Entering Image: Wood, Wind |

Kan Sinking Image: Water |

||

| Winter | Water "energy descending, a phase in the energy cycle at which the subject has obtained a maximum point of rest" |

Gen Stopping Image: Mountain |

Kun Compliant Image: Earth |

Although these correspondences seem natural to me, I haven't found them in any of the sources that I've consulted. The popular approach is to associate trigrams with Phases based on similarities in their nature images. We'll look at those correspondences when we discuss the After Heaven sequence and the Five Phases.

Before Heaven and the Hetu

As we've seen, the Before Heaven trigram sequence corresponds well to the Mutual Production sequence, and the Hetu diagram also corresponds well to the Mutual Production sequence. So it is reasonable to suppose that the arrangement of trigrams in the Before Heaven sequence should match the arrangement of numbers in the Hetu. The main difficulty is that Before Heaven is a circle, whereas Hetu is a more complex shape that you could view as a cross or as a set of concentric circles:

|

|

|

Hetu Map |

Before Heaven |

There are various ways the trigram assignments could be made. For example,

- The inner Hetu numbers 1 through 4 could map to the cardinal points in the Before Heaven, and the outer Hetu numbers 6 through 9 could correspond to the corners. Or you could take the exact opposite approach, mapping 1 through 4 to the corners and 6 through 9 to the cardinal points.

- The odd Hetu numbers, represented by white dots, could correspond to the cardinal points in the Before Heaven, and the even Hetu numbers, represented by black dots, could correspond to the corners of the Before Heaven. Or you could take the opposite approach and map the odd numbers to corners and even numbers to cardinal points.

Any of these approaches would reasonable, but none of them would yield the assignments discussed previously in "Hetu and Trigram Assignments." The reason is that Shao Yong's system incorporates a basic mistake. To determine the number for each trigram, he apparently overlaid the Luoshu numbers on the sequence of trigrams that result from generating the trigrams one line at a time:

This has the same effect as overlaying the Luoshu on the Before Heaven sequence:

The problems is that, as we shall see later in discussing the Luoshu, the Luoshu numbers correspond to the Five Phases in Mutual Conquest order. But the Hetu and Before Heaven sequences actually correspond to the Mutual Production order. Thus, if you use the Luoshu numbers to match Before Heaven trigrams with the Hetu, some of the trigrams get mapped to the wrong phase. As a reminder, here is a chart of Shao Yong's assignments:

The trigrams assigned to the lower and left branches work OK. But for the upper branch, the position of the Fire phase, the trigrams shown are ones that should really go with the Metal phase. And for the right branch, the position of the Metal phase, the trigrams shown are ones that should really go with the Fire phase. You can see this, for example, because the meanings of Kan and Xun emphasize falling and submission, which are not appropriate to the Fire phase; whereas the meanings of Dui and Qian emphasize joy and strong action, which are not appropriate to the Metal phase.

Recently I discovered a more plausible set of trigram assignments for the Hetu diagram. These are given by Chung Wu in his book The Essentials of the Yi Jing. His description is as follows:

What we need to demonstrate the correlation between the trigrams and the River map is to realign the numbers in the River map. The four numbers at the outside, i.e., 6, 7, 8, and 9, remain at their cardinal points. The four numbers at the inside move counterclockwise to their respective "corner positions," i.e. number 1 to lower right, number 4 to upper right, number 2 to upper left, and number 3 to lower left. Further, the four yang numbers, 1, 3, 7, and 9, are assigned to the four yang trigrams, respectively, [Gen], Zhen, Qian, and Kan . . . Similarly, the four yin numbers, 2, 4, 6, and 8, are assigned to the four yin trigrams, respectively, Dui, [Xun], Kun, and Li. [fn40]

In other words, you overlay the Before Heaven trigram cycle on the Hetu, map the outer Hetu numbers to the nearest trigram, and map the inner Hetu numbers to the trigrams in the corners.

Following is another view of the resulting assignments.

This gives you an arrangement where the Hetu, the Five Phases numbers, and the Before Heaven trigrams are all aligned consistently. Unfortunately, Wu does not explain if he came up with these assignments himself, or if they stem from some older source.

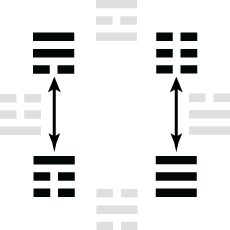

Before Heaven and Family Members

It turns out there is one rather interesting application where the Luoshu numbers do make sense with the Before Heaven sequence. The relationship has to do with the family roles of the trigrams. Here is the image of the Before Heaven sequence with the Luoshu numbers overlaid in it:

If you list the trigrams in order according to these Luoshu numbers, you get the following sequence:

This is a very interesting sequence from the point of view of the family roles of the trigrams. These family roles are described in the Shuogua. In Richard Rutt's translation, the passage reads as follows:

Qian is heaven, so means father;

Kun is earth, so means mother.

Zhen gets the first (bottom) line male,

so is called eldest son;

Xun gets the first (bottom) line female,

so is called eldest daughter.

Kan gets the second (middle) line male,

so is called the middle son;

Li gets the second (middle) line female,

so is called middle daughter.

Gen gets the third (top) line male,

so is called youngest son;

Dui gets the third (top) line female,

so is called youngest daughter.

—Shuogua III:10 [fn41]

The scheme arises from the assumption that yang (solid) lines are associated with males, and yin (broken) lines are associated with females. Thus, ![]() and

and ![]() are naturally understood to be Father and Mother. However, for the trigrams that have a mixture of yang and yin lines, it is the odd line out that determines the overall gender, and the position of that line (bottom, middle, or top) that determines if the child is eldest, middle, or youngest.

are naturally understood to be Father and Mother. However, for the trigrams that have a mixture of yang and yin lines, it is the odd line out that determines the overall gender, and the position of that line (bottom, middle, or top) that determines if the child is eldest, middle, or youngest.

Return now to the sequence of trigrams that we got by applying the Luoshu to the Before Heaven trigram sequence. If you add the family roles identified for each trigram in the Shuogua, you get:

Not only are the trigrams separated by gender, but they are ranked in a symmetrical way by age, from eldest female to youngest female and then from youngest male to eldest male. We'll refer to this as the "Before Heaven/Luoshu family ordering."

If modern scholars are correct, the Before Heaven arrangement was not created until Song Dynasty times, a thousand years after the trigram family relationships were laid out in the Shuogua. So the question becomes, could the application of the Luoshu numbers to trigram family roles have played some role in determining the Before Heaven arrangement? It is possible, but seems unlikely for a couple of reasons. In the first place, there is already a simpler rationale for the Before Heaven arrangement, based on the order of generating trigrams one line at a time.

In the second place, the Before Heaven/Luoshu family ordering places family members in a different sequence than I have encountered in any older sources. In the Shuogua, verse 4, the order is:

Thunder (eldest son)

Wind (eldest daughter)

Rain (middle son)

Sun (middle daughter)

Gen (youngest son)

Dui (youngest daughter)

Qian (father)

Kun (mother)

In verse 10, the order is

Qian (father)

Kun (mother)

Zhen (eldest son)

Xun (eldest daughter)

Kan (middle son)

Li (middle daughter)

Gen (youngest son)

Dui (youngest daughter) [fn42]

In the Mawangdui hexagram sequence, the upper trigrams in each column follow the sequence

Qian (father)

Gen (youngest son)

Kan (middle son)

Zhen (eldest son)

Kun (mother)

Dui (youngest daughter)

Li (middle daughter)

Xun (eldest daughter)

Also in the Mawangdui hexagram sequence, the lower trigrams in the first row follow the sequence

Qian (father)

Kun (mother)

Gen (youngest son)

Dui (youngest daughter)

Kan (middle son)

Li (middle daughter)

Zhen (eldest son)

Xun (eldest daughter) [fn43]

That's a lot of ways of organizing a family, without ever duplicating the Before Heaven/Luoshu family ordering!

Given that the Before Heaven/Luoshu family ordering doesn't seem to be used anywhere, and there is another explanation for how the Before Heaven cycle was derived, it seems likely that this ordering is simply a happy coincidence. Still, the coincidence is striking enough that I thought it worth mentioning here. Perhaps Jungians will ascribe it to Synchronicity.

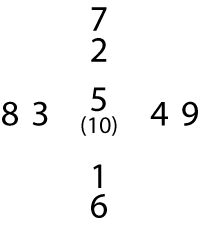

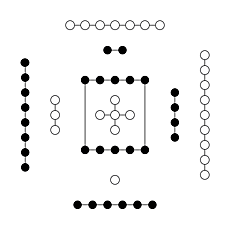

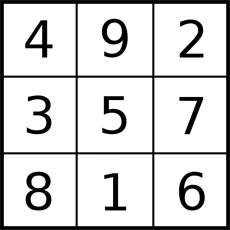

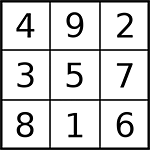

The Luoshu (Lo River Writing)

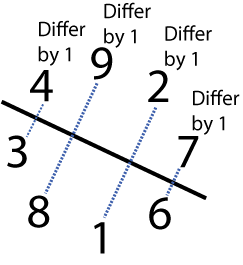

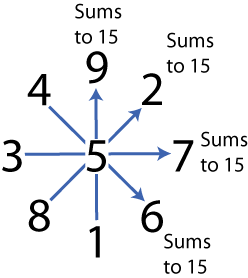

The Luoshu, or Lo River Writing, is a numeric diagram that arranges the numbers 1 through 9 into a magic square, such that any row, column, or diagonal adds up to 15. Each number is represented by groups of dots, where the white dots represent odd numbers and the black dots represent even numbers. You can also draw it as a grid of Arabic numerals as shown to the right below.

|

|

Frank J. Swetz's book Legacy of the Luoshu gives us the history of the diagram.[fn44] Legend ascribes the origin of the Luoshu to a turtle that appeared to the Sage King Yu on the banks of the Lo river in ancient times. The pattern of numbers originally appeared on the turtle's shell. However, the earliest surviving mentions of the Luoshu appear in Warring States time (5th-3rd century BC). The "nine luo" was mentioned by Zhuang Zi (369-286 BC). Another mention was in the I Ching, in the Great Commentary, I.11.8:

Heaven hangs out its (brilliant) figures from which are seen good fortune and bad, and the sages made their emblematic interpretations accordingly. The Ho gave forth the map, and the Lo the writing, of (both of) which the sages took advantage.[fn45]

Initially it appears that this pattern was kept secret, and sometimes referred to indirectly by other names such as the Nine Halls or the Nine Palaces. The numbers and their positions were finally disclosed by a Taoist named Zhen Luan (6th century AD), and a drawing of them was eventually published by the Taoist scholar Zheng Xuan (10th century AD).

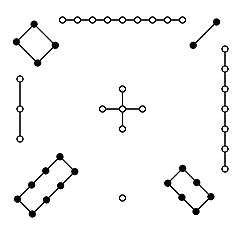

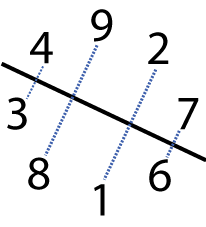

Aside from the "magical" property that the numbers sum to 15 in every direction, a few other features of the Luoshu are worthy of note:

- A number of different versions of this magic square can be created by rotating and/or flipping the pattern vertically or horizontally. The version that became popular in China is specifically a version that puts the largest number, 9, at the top center, and the smallest number, 1, at the bottom center.

- The odd numbers appear in the center and at the cardinal points (top, bottom, left, right). The even numbers all appear at the corners.

- The positions of the numbers, if read counterclockwise, correspond to the Mutual Conquest sequence of Five Phase (Wu Xing) theory. Five Phase theory associates each of the numbers with from one to ten with a particular Phase. In the Luoshu, the numbers that refer to the same Phase always appear adjacent to each other.

As Richard J. Smith says:

Thus, for example, metal (four and nine) overcomes wood (three and eight), wood overcomes earth (five), earth overcomes water (one and six), water overcomes fire (two and seven), and fire overcomes metal.[fn46]

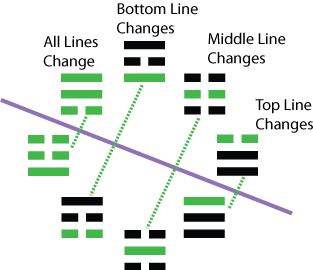

The following illustration shows how the Mutual Conquest sequence maps to the Luoshu:

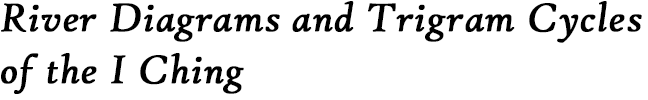

- If you divide the pattern with a diagonal line running from upper left to lower right, this reveals a bilateral symmetry between the two halves of the diagram. The numbers fall into the pairs 3 and 4, 8 and 9, 1 and 2, 6 and 7. In each pair, the numbers are separated by one, and the lower-left number in each pair the is the smaller one.

You don't find the same degree of bilateral symmetry if you divide the arrangement at any other angle. For example, if you rotate the line one notch clockwise, so it runs from between 4 and 9 down to between 1 and 6, the pairs of numbers that result are 4 and 9, 3 and 2, 8 and 7, 1 and 6.

Within these pairs, the numbers differ by 5, 1, 1, and 5, respectively, rather than each pair of numbers differing by the same amount. Further, within each pair, the higher number is sometimes on one side and sometimes on the other, rather than the lower numbers all being on one side and the higher numbers all on the other side. You get similarly lumpy results if you split the diagram at other angles. The only angle the gives nicely symmetric results is the one shown in the first of the preceding two images.

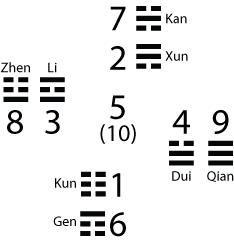

The After Heaven Trigram Sequence

The After Heaven trigram sequence (Houtiantu) is a circular arrangement of the eight trigrams (bagua). Since the Song dynasty (960–1279 AD), this arrangement has been ascribed to King Wen, the author of the Hexagram statements in the I Ching.[fn47] However, Richard Rutt says of the After Heaven sequence that "Nothing is known of its origin, but it is probably not much older than the Ten Wings."[fn48]

Ritsema and Sabbadini summarize a common view when they state that "the Sequence of Later Heaven or the Inner World Arrangement . . . applies to the human world we inhabit and to its natural cycles," as opposed to the Before Heaven sequence, which "reflects a cosmic order prior to the human world."[fn49] Similarly, Wilhelm says "The trigrams are taken out of their grouping in pairs of opposites [that is, the Before Heaven arrangement] and shown in the temporal progression in which they manifest themselves in the phenomenal world in the cycle of the year."[fn50]

The arrangement is described in the Shuogua, "Explaining the Trigrams," appendix of the I Ching (third century BC). This passage also correlates the trigrams with directions and seasons, as shown below:

In Bent Nielsen's translation, the Shuogua passage reads as follows:

The divine sovereign brings out [the ten thousand things] in Zhen, regulates them in Xun, makes them mutually visible in Li, causes them to be served in Kun, makes them happy in Dui, makes them fight in Qian, exhausts them in Kan, and completes them in Gen.

The ten thousand things are brought out in Zhen. Zhen is the east.

They are regulated in Xun. Xun is the southeast. As to being ‘regulated,’ it means the ten thousand things are adjusted and made even.

As to Li, it is brightness. The ten thousand things are made mutually visible. It is the trigram of the south. The sages faced south when they listened to the world (that is, held court), they turned towards the brightness and ruled. It is probably obtained from this.

As to Kun, it is the earth. The ten thousand things are all nourished by it, therefore it says, ‘‘causes them to be served in Kun.’’

Dui is midautumn. This is [the time] when the ten thousand things are content. Therefore it says, ‘‘makes them happy in Dui.’’

As to ‘‘fighting in Qian,’’ Qian is the trigram of the northwest. It means yin and yang are combating each other.

Kan is water. It is the trigram of due north. It is the trigram of fatigue. This is where the ten thousand things return. Therefore it says, ‘‘exhausts them in Kan.’’

Gen is the trigram of the northeast. This is where the ten thousand things reach the end and the beginning. Therefore it says, ‘‘Completes them in Gen.’’[fn51]

Along similar lines, Edward Hacker has written:

One can make some sense of the order of the trigrams in the Later Heaven Sequence since the meanings of the trigrams do coincide fairly well with their assigned seasons. [Zhen], Thunder, represents spring. This is the time that plants and trees start to become active; the bottom yang line pushing upward is akin to a seed beginning to grow. [Xun], Wind, represents late spring and early summer, the dispersing agent; the seeds are scattered. This Trigram also represents Wood, the symbol of growing things. [Li], Fire, appropriately symbolizes summer, the time of greatest heat. [Kun], Earth, represents late summer and early autumn. It is a time of fruitfulness. [Dui], Lake, represents autumn, a time of harvest, a time of joy. [Qian], Heaven, represents late autumn and early winter. It is the Trigram that symbolizes elderly men and the aging part of the year. At this time of year the yang fights a losing battle with the yin; heat gives way to cold. [Kan], Water, which generally stands for toil and trouble, symbolizes winter. It is at this time of the year that all creatures must make a special effort to survive. [Gen], Mountain, represents late winter and early spring, which is a time of stillness. It should be remembered that it is probable that the seasons in ancient China were regarded as occurring about a month and a half earlier than we do ours.[fn52]

Hacker's description reinforces the passage in the Shuogua and suggests the possibility that the After Heaven sequence was devised specifically to match the cycle of the seasons. But for various reasons, this is unlikely to be the complete explanation. Some of the choices that were made seem far from obvious. For example, is autumn really a more joyful time than spring, when green growth returns and the plants burst into flower? Further, since the main attribute of Kun, Earth, is receptivity, wouldn't it make more sense to place Kun at the time of the spring planting rather than in autumn? And does it make sense to put Qian, Heaven, the symbol of forceful action, at the start of winter, the time of quiescence?

More importantly, it turns out that the After Heaven trigram sequence has some hidden elements of structural order that are not explained by the seasonal analogies above. In his book, Hacker also presents some ideas about how the trigram structures could have given rise to the After Heaven arrangement. As we continue, we will review some of his ideas about the structure, along with observations of my own.

Disorder in the After Heaven Sequence

When you examine the After Heaven sequence, regarding the trigram structures only, the first thing that leaps out is that the trigrams at the top and bottom positions are complements of each other: ![]() and

and ![]() . At each position, the line has been changed from yang to yin or vice versa.

. At each position, the line has been changed from yang to yin or vice versa.

Aside from that observation, however, there is precious little that leaps out as orderly.

- The other opposite pairs of trigrams are not complements:

and

and  ,

,  and

and  , and

, and  and

and  .

. - On the right side, there is another pair of trigrams that are complements:

and

and  . But the corresponding pair on the left side are not complements:

. But the corresponding pair on the left side are not complements:  and

and  .

. - Vertically flipped trigrams are found adjacent to each other at the left and lower left:

and

and  . However, the other pair of vertically flipped trigrams are widely separated:

. However, the other pair of vertically flipped trigrams are widely separated:  at the upper left and

at the upper left and  at the far right.

at the far right. - If you look at the trigrams that have all yang lines below all yin lines, they are positioned opposite each other at the far left and far right:

and

and  . However, if you compare trigrams with all yin lines below all yang lines, they are not opposite to each other, but instead are both on the left:

. However, if you compare trigrams with all yin lines below all yang lines, they are not opposite to each other, but instead are both on the left:  and

and  .

.

In his own I Ching translation, John Blofeld's comment on the After Heaven sequence is:

It is difficult to see the logic of this arrangement; but, since it is found in all Chinese editions of the I Ching, I have included it here. It is said in China that beings above the level of humans are able to discover the meaning of this order, whereas humans are no longer able to do so.[fn53]

Shao Yong's Theory of Dynamic Trigrams

Shao Yong (1011–1077) was a Song Dynasty philosopher who is remembered as one of the most influential exponents of the xiangshu (school of images of numbers), or the approach to interpreting the I Ching based on patterns in the structure of the trigrams and hexagrams. In the Huang-chi ching-shih shu, he had this to say about the structure of the After Heaven sequence:

[Shao] also said: "Change" is what is meant by "the alternation of yin and yang." [Zhen] and [Dui] begin the interaction; therefore they are placed in the positions of morning and evening. [Kan] and Li interact to the utmost; therefore they are placed in the positions of midnight and noon. [Xun] and [Gen] do not interact, but their yin and yang is still mixed; therefore they are placed on the side among the functioning [trigrams]. [Qian] and [Kun] are pure yang and pure yin, and so are placed in non-functioning positions.

He also said: [Dui], Li and [Xun] get the majority of yang [lines]; [Gen], [Kan] and [Zhen] get the majority of yin. For this reason they constitute the functioning of Heaven and Earth. [Qian] is completely yang, and [Kun is completely yin. Therefore they do not function.[fn54]

This rather terse passage proposes a very interesting, and I think partially correct, theory as to the organization of the After Heaven sequence. The key to understanding it is this remark by Joseph A. Adler:

"Functioning" here and in the following passages refers to trigrams that are dynamic or changing.[fn55]

The theory basically is that After Heaven places the most dynamic trigrams in the most dynamic positions. But what determines which trigrams are most dynamic, and which positions are most dynamic?

The key point about dynamic trigrams is that yang (solid) lines tend to rise, whereas yin (broken) lines tend to fall. It appears that a trigram is considered dynamic if it has a mix of yang and yin lines, especially if the yang lines are below the yin ones, so the yang and yin lines are moving toward each other. The dynamic nature of the trigram is even further enhanced if the yang and yin lines are mixed so as to reverse polarity twice rather than just once, by going from yang to yin and back to yang, or yin to yang and back to yin. Based on this rationale, the trigrams can be classified into pairs, which are ordered below from the most dynamic to the least dynamic:

and

and  (polarity reverses twice)

(polarity reverses twice) and

and  (yang below yin)

(yang below yin) and

and  (yin below yang)

(yin below yang) and

and  (all yang or all yin)

(all yang or all yin)

With regard to the positions, Shao Yong seems to have felt that the cardinal positions (South, North, East, West) are more dynamic than the corners. Among the cardinal positions, Shao treats South and North, the top and bottom positions, as more dynamic than East and West.

The theory works well as far as it goes, but it does not explain the After Heaven sequence completely. For example, within each pair of trigrams, which one is to be considered more dynamic? Is ![]() more dynamic than

more dynamic than ![]() , and if so, why? Because it contains more yang lines? If so, then why does Shao place

, and if so, why? Because it contains more yang lines? If so, then why does Shao place ![]() at the East, and

at the East, and ![]() at the West, despite the fact that he seems to regard the Eastern positions are more dynamic than the Western ones?

at the West, despite the fact that he seems to regard the Eastern positions are more dynamic than the Western ones?

Also, if you apply Shao's theory to the After Heaven sequence, it becomes clear that the corner positions are grouped differently from the cardinal positions. The matching trigrams in the cardinal positions are placed opposite to each other: ![]() to the North and

to the North and ![]() to the South;

to the South; ![]() the East, and

the East, and ![]() to the West. But the matching trigrams in the corner positions and placed both on the left or both on the right:

to the West. But the matching trigrams in the corner positions and placed both on the left or both on the right: ![]() to the Northeast and and

to the Northeast and and ![]() to the Southeast;

to the Southeast; ![]() to the Northwest and

to the Northwest and ![]() to the Southwest.

to the Southwest.

|

|

|

| Paired trigrams in the cardinal positions are placed opposite each other. | Paired trigrams in the corner positions are placed both on the left side or both on the right side. |

Zhu Xi, in his Introduction to the Study of the Changes, includes several quotes from his friend Ts'ai Yüan-ting to explain these details of Shao's theory. Unfortunately, Ts'ai Yüan-ting's comments have rather the flavor of ad hoc rationalizations, with each one created to meet a special case. Thus, Ts'ai says:

Having examined this chart, I would explain it further. As for [Zhen] in the East and [Dui] in the West: Yang chiefly progresses, so we take the elder as prior and place him on the left. Yin chiefly retires, so we take the younger as honored and place her on the right. As for [Kan] in the North: it is in the process of progressing. Li in the South is in the process of retreating. The male in the North and the female in the South shelter each other's domiciles. These four are all placed in the cardinal positions of the Four Directions, and are the trigrams that perform services. However, [Zhen] and [Dui] initiate, and [Kan] and Li complete. [Zhen] and [Dui] are light and [Kan] and Li are heavy.

[Qian] in the Northwest and [Kun] in the Southwest are father and mother, already old and retired, occupying non-functioning places. However, the mother is intimate and the father is noble. Therefore [Kun] is something like half-functioning, and [Qian] is completely non-functioning.

[Gen] in the Northeast and [Xun] in the Southeast are the youngest male after his advancement and the oldest female before her retiring. Therefore they also are both non-functioning. However, the male has not yet been taught, and the female is about to travel [leave home to be married]. Therefore [Xun] has a slight tendency toward functioning, while [Gen] is completely non-functioning. The four all occupy the non-cardinal positions in the four corners. However, the occupants of the East [youngest son and oldest daughter] are not yet functioning, while the occupants of the West [father and mother] are no longer functioning.[fn56]

Ts'ai's comments make use of the family roles of the trigrams, which we will discuss in more detail in the next section. Additionally, Ts'ai identifies the left, or Eastern, positions as more dynamic because they are associated with the Spring of the year when activity is increasing; and identifies the right, or Western, positions as less dynamic because they relate to Autumn when activity is declining.

Even with these major assumptions, Ts'ai has to introduce additional considerations such as "the mother is intimate and the father is noble. Therefore [Kun] is something like half-functioning, and [Qian] is completely non-functioning." But it is exceedingly unclear why the father is more noble than the mother, or why being noble would make him non-functioning.

Ts'ai's rationalizations aside, it appears that Shao's theory is simply incomplete. It gives a compelling rationale for certain aspects of the After Heaven sequence, but cannot account for the details.

Family Groupings in the After Heaven Sequence

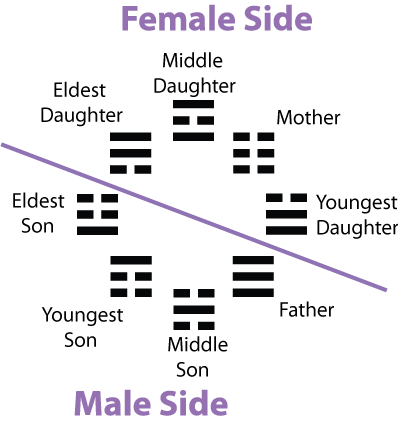

Edward Hacker has pointed out that the trigram family roles from the Shuogua show up in the After Heaven trigram sequence. When you consider the trigrams in terms of their family roles, you can see that the male trigrams have been segregated from the female trigrams.[fn57]

If I calculate correctly, only about one in ten of the possible trigram arrangements have this property of segregating the male trigrams from the female ones.[fn58] So on the face of it, this property of the After Heaven arrangement is unlikely to be accidental.

However, if you view the sequence purely from the standpoint of family relationships, it is quite odd. The mother and daughters are not ordered by age, nor are the father and sons. Nor is the ordering of the females at all similar to the ordering of the males. So it appears that family relationships cannot be the sole or primary ordering principle in the After Heaven sequence.

Supposing you combine the property of segregated genders with Shao Yong's rationale of positioning the dynamic trigrams in the most dynamic positions. Would these two theories together be sufficient to explain the After Heaven sequence? No, because there are multiple arrangements that fulfill both the requirements of Shao Yong's theory and the requirement to segregate genders. For example, you could flip the positions of the Father and Youngest son, or the positions of the Mother and Eldest Daughter. Remember that, without Ts'ai Yüan-ting's additions, Shao Yong's theory doesn't give an explanation of which corner positions are more dynamic than others.

However, the After Heaven sequence has more patterns hidden within it. Perhaps these will lead us to a more complete understanding of the sequence.

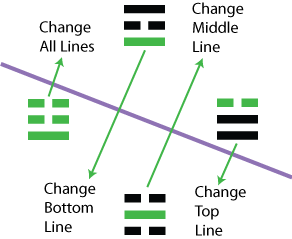

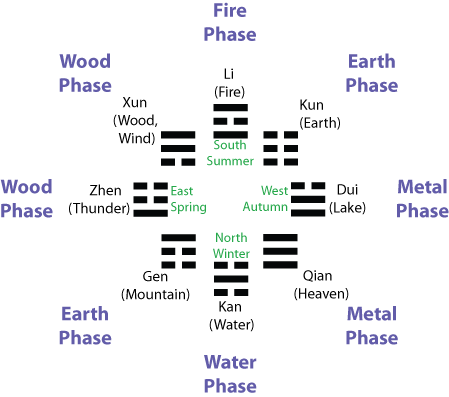

Bilateral Symmetry in the After Heaven Sequence

We saw in the previous section that the female trigrams are separated from the male trigrams by a diagonal line from upper left to lower right. If you compare the trigrams that are directly across this line from each other, something interesting happens:

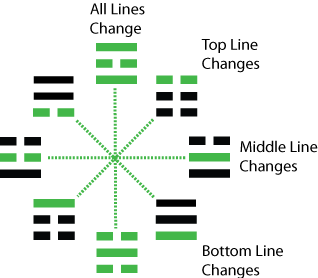

In other words, as you proceed along the dividing line, you encounter these pairs which have the following relationships:

and

and  , a pair where every line changes when you go from one trigram to the other.

, a pair where every line changes when you go from one trigram to the other. and

and  , a pair where only the bottom line changes.

, a pair where only the bottom line changes. and

and  , a pair where only the middle line changes.

, a pair where only the middle line changes. and

and  , a pair where only the top line changes.

, a pair where only the top line changes.

The sequence of changes (all lines, bottom line, middle line, and top line) is an orderly one.

Further, this rationale combines in an interesting way with Shao Yong's theory of dynamic trigrams. If you start from the trigrams that Shao Yong assigned to the cardinal points, and change the lines in the order shown, than this forces the remaining trigrams to be placed in the corners in the rather odd arrangement that they do occur in the After Heaven sequence.

So at this point the After Heaven sequence is starting to make sense. At least we've identified a combination of theories that generate the sequence completely. However, the sequence has at least one more mystery that we have not yet addressed.

Radial Symmetry in the After Heaven Sequence

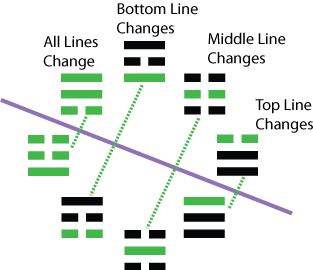

The next structural pattern resembles the previous one, except that it is organized around the point in the middle of the diagram.

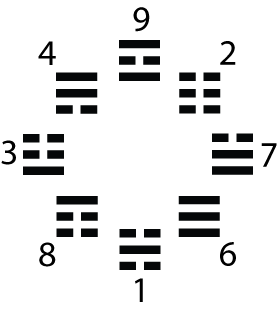

As you proceed clockwise around the circle, starting from the top position, if you compare each trigram with the trigram in the opposite position, the following sequence of relationships emerges:

and

and  , a pair where every line changes when you go from one trigram to the other.

, a pair where every line changes when you go from one trigram to the other. and

and  , a pair where only the top line changes.

, a pair where only the top line changes. and

and  , a pair where only the middle line changes.

, a pair where only the middle line changes. and

and  , a pair where only the bottom line changes.

, a pair where only the bottom line changes.

After Heaven and the Luoshu

Elizabeth Moran and Joseph Yu write that "The Hou Tian or After Heaven bagua is related to the Luoshu. The Hou Tian sequence of trigrams denotes motion, change, and transformation."[fn59]

If you compare the After Heaven trigram sequence with the Luoshu numbers, at first they seem to have little in common.

If you assign the trigrams to their matching Luoshu numbers, and then arrange them in their numerical sequence, the result is almost complete disorder. The only feature of note is that the trigrams for 1 and 9 are complements of each other.

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

Yet strangely, the After Heaven sequence and the Luoshu do share the same patterns of symmetry. Both have bilateral symmetry along the upper left to lower right diagonal.

|

|

And both have a radial symmetry around the central point.

|

|

The analogy is of course a fairly weak one, but is worth noting in light of the insistence by authors such as Moran and Yu that the Luoshu and After Heaven sequence are related.

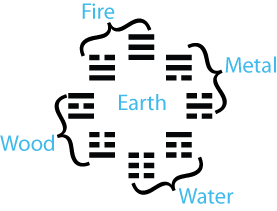

After Heaven Sequence and Five Phases

In the previous discussion of Before Heaven and the Five Phases, I noted that trigrams are traditionally associated with the Five Phases based on similarities in the associated nature elements. For example, because the Li trigram is associated with fire, it gets equated to the Fire Phase in the Five Phase system. Based on this approach, the Five Phases are associated with the After Heaven trigram sequence in the positions shown below.[fn60]

A few of the assignments are not obvious. The nature images for Zhen (Thunder) and Qian (Heaven) do not resemble any of the Five Phases. Also, Dui (Lake), which you would think would be grouped with the Water Phase, is placed in the Metal phase instead. So I think an additional goal of these Five Phase/trigram assignments is to put the Five Phases in an order resembling the Mutual Generation sequence: Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water. The only deviation is that Earth is shown in two positions, after both Water and Fire. This does not place too great a strain on the Five Phase system. Because Earth is the balanced state, it is sometimes said to occur at the end of Summer, when yang has stopped increasing but has not yet started to decrease. You could argue that the end of Winter is a similar balancing point, where yin is no longer increasing but has not yet started to decrease. Indeed, in the Five Phase system, Earth is sometimes said to occur as a brief transition period between each of the other four seasons.

The following table shows the main attributes of the Five Phases and the meanings of the trigrams traditionally associated with those Phases in the After Heaven sequence[fn61]:

SEASONS |

Five Phases |

Eight Trigrams |

| Spring | Wood |

Zhen |

Xun Temperament: Entering Image: Wood, Wind |

||

| Summer | Fire

Full Yang Ascending Blooming |

Li Temperament: Connecting Image: Fire |

| Summer/Autumn transition, Winter/Spring Transition |

Earth Yin/Yang balance Stabilizing (representing harmony) Ripening |

Kun Temperament: Compliant Image: Earth |

Gen

Temperament: Stopping Image: Mountain |

||

| Autumn | Metal

New Yin Contracting and interior Withering |

Dui Temperament: Pleasing Image: Lake |

Qian Temperament: Strong Image: Heaven |

||

| Winter | Water |

Kan |

The main problems with this set of Five Phase/trigram assignments are:

- In the Five Phase system, the Earth Phase is assigned the Cardinal direction of Center. But the corresponding trigrams in the After Heaven sequence appear at the Northeast and Southwest positions. Also, while the Earth Phase represents a balance of yin and yang energies, the chosen trigrams are decidedly yin (compliant and stopping).

- In the Five Phase system, the Metal Phase is contracting, interior, and withering. But the assigned trigrams are Pleasing and Strong.

Another oddity relates to the Luoshu, which many commentators associate with the After Heaven sequence. As we have seen previously, the Luoshu is a numeric diagram, and when the numbers of the Five Phases are mapped to this diagram, you get the Mutual Conquest order rather than the Mutual Production order. If you then apply these Five Phase assignments to the trigrams that are in the same positions as the Luoshu numbers, you get the assignments shown below.

|

|

This set of assignments has its own set of problems:

- The Earth trigram, meaning Compliance (a very yin characteristic), is placed in the Fire Phase, which means Full Yang, Ascending, and Blooming.

- The Gen trigram, meaning Stopping, is placed in the Wood Phase, which means New Yang, Expanding, and Sprouting.

- The Qian trigram, meaning Strong, is placed in the Water Phase, which means Full Yin, Descending, and Dormant.

Previously we also discussed a set of trigram assignments based on applying the Five Phases Mutual Production sequence to the Before Heaven trigram cycle. As a reminder, that arrangement is shown below.

|

Before Heaven with Five Phases |

This arrangement associates the trigrams with the Five Phases as shown below:

Water |

Water |

Metal |

Metal |

Wood |

Wood |

Fire |

Fire |

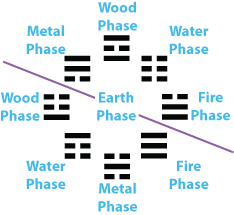

If you apply this set of trigram/Phase assignments to the After Heaven cycle, you get the following arrangement:

|

After Heaven with Five Phase Assignments from Before Heaven |

The After Heaven sequence is shown above with the line that divides the Female trigrams from the Male ones. With this division in mind, you can see in the following diagram that the Female trigrams follow the Mutual Conquest sequence, whereas the Male trigrams follow the Mutual Production sequence.

Of course, the mind boggles if you try to imagine someone planning this set of cycles in the After Heaven sequence, on top of all the other patterns that we've already found in in that sequence. The only inelegant touch is that both cycles have to jog rather sharply inward toward the center to include the Earth element. This is a feature that you will generally find in pictures that portray the Mutual Conquest and Mutual Production sequences when the Earth element is placed in the center.

|

Mutual Production with Earth in the Center |

In the unlikely event that someone deliberately included this pattern of double cycles in the After Heaven sequence, what would it mean? Well, it associates females with the Mutual Conquest cycle and males with the Mutual Production cycle. That seems a bit backwards since men are more given to marching off to war (conquest), and women are the ones who give birth (production). But rather than this being specifically a comment on the sexes, perhaps it is simply a reflection of the idea that yang is positive and yin is negative. That (un-Daoist) tendency to view the yin as negative is one that does seem to be reflected in some of the I Ching's hexagram and line judgments.

The Mystery of After Heaven

In concluding our study of the After Heaven sequence, it is worth pondering whether any of the structural patterns we have observed were actually intentional. Having several theories of the structure, no one of which is sufficient to form a whole explanation, is certainly less satisfying than having a single, simple theory that explains the whole thing at one go. Again, we have to ask ourselves: If the originator of the After Heaven sequence deliberately contrived to include all of these properties (placing dynamic trigrams in dynamic positions, segregating males from females, as well as displaying bilateral symmetry and radial symmetry), doesn't that make him or her the most insanely clever person in the history of the world?

If on the other hand the arrangement is a random one, then what are the odds it would include several interesting types of order in it? I don't know a way to calculate that. The I Ching in general does tend to tease us with structures that seem on the border between being orderly and random. Edward Hacker ended his examination of structure in the After Heaven sequence with these remarks, which apply equally as well to my own analysis:

There is no evidence that the ancient Chinese constructed the Later Heaven Sequence by using any of the formal orders mentioned above, or even that they were aware of these orders. But the fact that these orders can be found in the Later Heaven sequence may suggest that some formal considerations were given to its construction. [fn62]

If any of the structural patterns in the After Heaven cycle are deliberate, this raises the question of what the author was trying to convey with this sequence:

- Placing the most dynamic trigrams in the most dynamic positions seems to maximize the idea of change. It is as if the sequence represents the maximum of volatility. Or, if you think of work as the ability to effect change, then perhaps this arrangement implied an idea of maximum power and effectiveness.

- Segregating the male and female trigrams could imply that the author saw this distinction as an important one for interpreting hexagrams.

- The bilateral and radial orders, which each work by changing upper, middle, and lower lines one at a time, could serve to emphasize a differing significance for each of these line positions. For example, the lower line is sometimes interpreted as Earth, the upper line as Heaven, and the middle line as Humanity.[fn63]

Once the positions of the trigrams in the After Heaven cycle are fixed, those positions suggest the directions and seasons corresponding to each trigram. Such associations can lead to further associations, eventually giving rise to the long list of trigram attributes in the Shuogua.

Conclusions

We've reviewed four ancient and medieval diagrams and looked at ways they relate to each other, as well as how they relate to Five Phase theory and trigram family relationships. Given that the origins of the various figures are uncertain, can we draw any conclusions about which relationships are intentional?

It seems plausible that the Luoshu diagram could have something to do with the Five Phases. As we noted before, the Luoshu diagram could be rotated or reflected various ways while remaining a magic square. Possibly the current version was chosen because it served to illustrate the Mutual Conquest sequence. Alternatively, the numbers associated with the Five Phases could have been drawn from the Luoshu.

It's not so clear that the Luoshu diagram and the After Heaven sequence are related. We have noted the presence of a bilateral symmetry and a radial symmetry in both. However, when you associate the Luoshu numbers with the After Heaven trigrams, the results appear to be nonsensical.

The Hetu diagram shows a strong correspondence to Five Phase theory, grouping together the numbers for each phase and displaying them in Mutual Generation sequence. I would assume that Hetu was developed specifically to illustrate the Five Phase theory.

The Before Heaven trigram sequence may have resulted from Song Dynasty experiments with placing the trigrams and hexagrams in a regular sorting order. A side effect of this approach is that the trigram sequence fits naturally with the Mutual Generation sequence in Five Phase theory. The application of the Luoshu numbers to the Before Heaven sequence to yield the Trigram Family assignments strikes me as a happy coincidence, though there's a slight chance that the Luoshu influenced the design of the Before Heaven sequence.

The many patterns that we have observed in the After Heaven trigram sequence are unlikely to all be intentional. However, they might be side effects of some simpler ordering scheme that we have not yet discovered.

Regarding the Zhouyi (the I Ching hexagram and line texts), there is no direct evidence that it was created with any awareness of trigram theory, Five Phase theory, family members, or any of the cosmic diagrams or trigram sequences. However, these concepts are all natural developments of Yin Yang theory, which was just being born when the Zhouyi was first written. As such, it is possible that the cosmic diagrams could shed useful light on hexagram and line meanings that are considerably older.

Overall, the cosmic diagrams and trigram sequences are examples of how enduringly suggestive and fruitful the I Ching has been in inspiring new interpretive ideas. Their compelling visual form has also added to the mystique of the I Ching and will doubtless continue to intrigue people for a long time to come.

Notes

fn01. Rutt says (pp. 97-98), "Many, perhaps most, sinologists now believe that the hexagrams are older than the trigrams," but also points out "Much interpretation of the oracles today, following Wilhelm, depends on constituent and nuclear trigrams. The validity of such interpretations does not depend on the historical priority of the trigrams: given the modern diviner's understanding of the nature of Zhouyi, the mere fact that a hexagram can be analysed into two or more trigrams justifies using them in prognostication."

fn02. Huang, The Numerology of the I Ching.

fn03. Wikipedia, "Fuxi".

fn04. Smith, pp. 79-80. I have added the dates shown in brackets.

fn05. Smith, pp.79-80. Regarding the date of the Great Commentary: "One of these commentaries, the Xici 繋辭, also called the Great Commentary 大傳, is perhaps the most important source we presently have for exploring early Chinese cosmology. Given that a silk manuscript version of it dating from 168 BC was found at the Mawangdui site in Changsha in 1973, we have at least a terminus ad quem for its compilation." Roger T. Ames, The Great Commentary (Dazhuan 大傳) and Chinese natural cosmology. From International Communication of Chinese Culture May 2015, Volume 2, Issue 1, pp 1–18. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40636-015-0013-2 on 6/14/2018. Richard J. Smith states that the Great Commentary "probably assumed something close to its final form about 300 BCE" (Smith, p. 38) and also says it was "composed in the late Zhou and probably refined in the early Han dynasty (206 BcE-222 CE)" (Smith, p. 8).

fn06. Rutt, p. 415.

fn07. Rutt, p. 415.

fn08. Wikipedia, "Taijitu."

fn09. Yoke, Li, Qi, and Shu, p. 18.

fn10. Needham, Volume 2, p. 254.

fn11. Yoke, Li Qi, and Shu, p. 18. I have reordered the rows in his table to match the Cosmogonic order.

fn12. Olson, p. 64.

fn13. Yoke, Li, Qi, and Shu, p. 18.

fn14. Huang, The Numerology of the I Ching, p. 27; Olson, Book of Sun and Moon (I Ching), Volume I, p. 63.

fn15. Tr. Rutt, p. 418.

fn16. Ritsema and Sabbadini, p. 58.

fn17. I haven't found a succinct estimate of the date of the Shuogua, but the following quotes are pertinent. "The eighth of the Ten Wings, Explaining the Trigrams (Shuo gua), consists of remarks on the nature and meaning of the eight trigrams (bagua), the permutations of which form the sixty-four hexagrams. Much of this is couched in terms of yin-yang dualism and the theory of the wuxing (five elements) and so probably dates from the early Han era (third century B.C.). It is among the latest of the exegetical materials included in the Changes," according to Lynn, p. 3. "The 8th Wing is composed of two documents combined into one . . . The second document (Part II) is apparently an amalgam of several sources and may have originated as much as 200 years later, though it includes ideas that are known to have been in existence earlier, for they appear in the Zuo Commentary," according to Rutt, pp. 439-440.

fn18. Wilhelm, pp. 265-266.

fn19. Nielsen, p. 137. Bracketed dates added.

fn20. Rutt, p. 440.

fn21. Nielsen, p. 137.

fn22. Huang, pp. 13-14.

fn23. Wikipedia, "Taijitu."

fn24. Wilhelm and Wilhelm, pp. 115-119; Yoke, pp. 46-49; Wei, pp. 26-31; Huang, p. 39; Schoenholtz, p. 52.

fn25. Hacker, p. 37.

fn26. Schuyler Camman offers a similar argument about differences between the I Ching and a true binary system. See Camman, pp. 585-589. Skepticism is also expressed in Moran and Yu, p. 249.

fn27. Yoke, p. 56.

fn28. Yoke, pp. 57-58.

fn29. Rutt, discussion of Bagua numerals, pp. 98-100: "When the signs are numerals, they are easily recognized Chinese figures from 1 to 9, in groups such as 766718 . . . some groups of six figures cannot be obtained by the divination procedures how known, which give only the four numbers 6, 7, 8, and 9." Fendos says the Bagua numerals, which he calls numeric gua, were produced using the numbers 1 and 5 through 9 (Fendos, p. 7).

fn30. Rutt, p. 162.

fn31. Rutt, pp. 114-117.

fn32. Rutt, p. 90.

fn33. Rutt, pp. 99-93.

fn34. Needham, pp. 342-343.

fn35. Fendos, p. 22. Hacker and Cleary are examples of authors who both use binary notation to represent trigrams and hexagrams.

fn36. Rutt, p. 441.

fn37. Rutt, p. 441.

fn38. Swetz, p. 32.

fn39. A virtually identical description of the elements is given in the Chinese Buddhist Encyclopedia, "Wu Xing."

fn40. Wu, pp. 39-40.

fn41. Rutt, p. 447. I have added the trigram pictures.

fn42. Rutt, pp. 446-447.

fn43. Camman, p. 579.

fn44. Swetz, pp. 12-16.

fn45. Legge, p. 374. Legge numbers the verse as 73 rather than 8.

fn46. Smith, p. 81.

fn47. Nielsen, p. 131.

fn48. Rutt, p. 440.

fn49. Ritsema and Sabbadini, p. 58.

fn50. Wilhelm and Baynes, p. 268.

fn51. Nielsen, p. 136.

fn52. Hacker, pp. 39-40.

fn53. Blofeld, I Ching, p. 218.

fn54. Shao Yong, quoted in Zhu Xi, p. 42.

fn55. Joseph Adler (ed.), footnote in Zhu Xi, p. 42.

fn56. Ts'ai Yüan-ting, quoted in Zhu Xi, p. 43.

fn57. Hacker, p. 40.

fn58. Possible trigram arrangements are 8! or 40,230. For male/female segregated arrangements, I calculate the possibilities as 4! * 4! * 8 or 4,068.

fn59. Moran and Yu, p. 57.

fn60. Wikipedia, "Bagua." Also Chinese Buddhist Encyclopedia, "Wu Xing."

fn61. Attributes of the Five Phases are from the Chinese Buddhist Encyclopedia, "Wu Xing." Trigram temperaments are from Rutt, p. 441.

fn62. Hacker, p. 41.

fn63. Shuogua I:2 appears to be a reference to this scheme of identifying Heaven, Earth, and Man with the line positions in a trigram, though the passage does not make it clear which line corresponds to Heaven, which to Earth, and which to Man. (Rutt, p. 445) Wilhelm's commentary states that "The lowest place in the trigram is that of earth; the middle place belongs to man and the top place to heaven." (Wilhelm. p. 265)

Bibliography

Blofeld, John. I Ching: The Book of Change. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1968.

Camman, Schuyler. Chinese Hexagrams, Trigrams, and the Binary System. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 135, Number 4, December 1991 pp. 576-590.

Chinese Buddhist Encyclopedia, s.v. "Wu Xing." http://www.chinabuddhismencyclopedia.com/en/index.php?title=Wu_Xing. Retrieved 6/29/2018.

Cleary, Thomas. I Ching Mandalas: A Program of Study for The Book of Changes. Boston & Shaftesbury: Shambhala Publications, Inc., 1989.

Fendos, Paul G., Jr. The Book of Changes: A Modern Adaptation & Interpretation. Wilmington, Delaware: Vermont Press, 2018.

Hacker, Edward. The I Ching Handbook: A Practical Guide to Personal and Logical Perspectives from the Ancient Chinese Book of Change. Brookline, Massachusetts: Paradigm Publications, 1993.

Huang, Alfred. The Numerology of the I Ching: A Sourcebook of Symbols, Structures, and Traditional Wisdom. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions International, 2000.

Legge, James. The I Ching. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1963.

Lynn, Richard John. The Classic of Changes: A New Translation of the I Ching as Interpreted by Wang Bi. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Moran, Elizabeth, and Master Joseph Yu. The Complete Idiot's Guide to the I Ching. Indianapolis: Alpha Books, 2002.

Needham, Joseph, with the research assistance of Wang Ling. Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 2: History of Scientific Thought. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1969.

Nielsen, Bent. Cycles and Sequences of the Eight Trigrams. Journal of Chinese Philosophy 41:1-2 (March–June 2014), 130–147.

Olson, Stuart Alve. Book of Sun and Moon (I Ching), Volume I. Phoenix, AZ: Valley Spirit Arts, 2014.

Ritsema, Rudolf, and Shantena Augusto Sabbadini. The Original I Ching Oracle: The Pure and Complete Texts with Concordance. London: Watkins Publishing, 2007.

Rutt, Richard. The Book of Changes (Zhouyi). London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2002.

Schoenholtz, Larry. New Directions in the I Ching: The Yellow River Legacy. Secaucus, New Jersey: University Books, 1975.

Smith, Richard J. Fathoming the Cosmos and Ordering the World: The Yijing (I-Ching, or Classic of Changes) and Its Evolution in China. Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2008.

Swetz, Frank J. Legacy of the Luoshu: The 4,000 Year Search for the Meaning of the Magic Square of Order Three. Chicago and La Salle, Illinois: Open Court Publishing Company, 2002.

Wei, Henry. The Authentic I Ching. North Hollywood, California: Newcastle Publishing Co., Inc., 1987.

Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, s.v. "Bagua." https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Bagua&oldid=848396196 (accessed July 5, 2018).

Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, "Fuxi." https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Fuxi&oldid=846929889 (accessed July 5, 2018).

Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, "Taijitu." https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Taijitu&oldid=848241532 (accessed July 5, 2018).

Wilhelm, Richard, and Cary F. Baynes (translators). The I Ching or Book of Changes. New York: Princeton University Press, 1980.

Wilhelm, Hellmut, and Richard Wilhelm. Understanding the I Ching: The Wilhelm Lectures on the Book of Changes. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Wu, Chung. The Essentials of the Yi Jing. St. Paul, Minnesota: Paragon House, 2003.

Yoke, Ho Peng. Li, Qi, and Shu: An Introduction to Science and Civilization in China. Minneola, New York: Dover Publications, 2000.

Zhu Xi, translated by Joseph A. Adler. Introduction to the Study of the Changes (Yixue qimeng 易學啟蒙). Corrected edition, 2017. From the author's website at http://www2.kenyon.edu/Depts/Religion/Fac/Adler/writings.htm. Retrieved 6/14/2018.

Picture Credits

A number of the pictures are from Wikimedia Commons, as listed below:

![]() https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taijitu_-_Small_(CW).svg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taijitu_-_Small_(CW).svg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Magic_Square_Lo_Shu.svg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Magic_Square_Lo_Shu.svg

https://en.wikipedia.org/

https://en.wikipedia.org/

https://commons.wikimedia.org/

https://commons.wikimedia.org/

https://commons.wikimedia.org/

https://commons.wikimedia.org/

https://commons.wikimedia.org/

https://commons.wikimedia.org/

Other illustrations are original or were created by adding elements to the pictures listed above.

Revisions